On an unseasonably warm afternoon in early March, four worker-volunteers stood at the employee entrance/exit of a major manufacturer in Greer, South Carolina, donning yellow reflective vests, clipboards, and fliers.

A trickle of cars leaving the facility shortly past five quickly turned into a steady stream around 5:30pm. “Workers are coming together to fight for better conditions and power on the job. Does that sound like something you want to be a part of?” one of the volunteers said to a worker leaving the plant, handing her a flier with a short message and information on a workers assembly meeting later that week. The worker’s enthusiastic “Oh hell yeah” quickly moved into an exchange of contact information for a more extensive follow-up conversation.

These four volunteers were part of a five-day effort organized by the Southern Workers Assembly (SWA) to blitz workplaces across Spartanburg County, South Carolina from March 9 through March 13. In total, teams distributed nearly 1,500 leaflets and had conversations with workers at nearly two dozen major employers from various sectors across the county, from auto parts manufacturers and warehousing hubs to the public sector. Nearly 70 workers shared contact information with worker-volunteers during the blitz, and 30 from various sectors attended the Spartanburg Workers Assembly meeting that concluded the five days of outreach.

The initiative borrowed a tactic that is not uncommonly utilized by unions during an organizing campaign—a multi-day, concentrated push of workplace outreach, usually focused on one employer or a singular sector—and broadened it out, targeting major employers irrespective of sector. Worker volunteers were publicly recruited from the Spartanburg area and other nearby cities. Another handful supported the blitz remotely by helping with follow-up calls to workers. In that way, the effort was imbued with a movement-building spirit that went beyond traditional organizing confined to a singular workplace.

An immediate objective of the effort was to broaden the base of the emerging workers assembly in Spartanburg, identifying ‘live wires’—workers that resonate with the message around workers building organization and a movement to fight to transform our workplaces and communities. But beyond that, the blitz model offers a path forward for workers to offensively address the crisis of working-class organization—acute in the South and true across the United States—in a hostile political period.

I-85: An economic powerhouse

Spartanburg County sits in the Upstate region of South Carolina, nestled alongside Interstate 85 —the 666-mile-long highway that begins just south of Richmond, VA, and ends in Montgomery, AL.

In a July 2024 article about the economic impacts of the interstate, Site Selection Magazine compared its importance to the South’s economy to “what the Transcontinental Railroad was to the entire country 150 years ago,” adding that the corridor is the “region’s undisputed king of commerce.” The Greenville-Spartanburg metro area illustrates this point exceptionally well.

What was once a center of textile production in the 1800s and 1900s, has today been transformed into a center of goods manufacturing, particularly in the auto industry. What attracted capital investments from textile manufacturers 100 years ago— abundant land and natural resources, low costs, cheap labor, and low union density—are in many ways the same forces driving the manufacturing boom in the area today.

Around the same time that the neoliberal trade regime was decimating the textile industry in South Carolina and elsewhere, BMW announced plans to open a major manufacturing hub in the area. Built in 1994, the plant now employs 11,000 workers and produces 1500 vehicles daily (60% of which are shipped overseas via the dry inland port in Greer which is connected by rail to the Port of Charleston). BMW has invested over $13 billion into the plant since its construction.

While BMW stands out as the largest employer, many other major production and warehousing operations have opened in the area over the last 10 years. Given the tremendous amount of production that now occurs in Greenville-Spartanburg, and its reliance on the Greer inland port to quickly move goods to and from the Port of Charleston, the area is a prime bottleneck for domestic and international commerce.

From 2023-2024, over $2 billion in capital investments came into the Greenville-Spartanburg area, second only along the I-85 corridor to Fulton County, GA, home of Atlanta. The area is among the top 10 growing multi-county metropolitan areas in the country, and in Spartanburg County, the manufacturing and logistics industries account for nearly a third of employment, well above the national average of about 13%. However, wages for manufacturing workers are well below the national average, with workers taking home around $1380 per week, on average, compared to a national average of nearly $1600 per week.

South Carolina has the second lowest union density in the country, with just 2.8% of workers belonging to unions (neighboring North Carolina takes last place with 2.4% density). There has not been a successful effort to win a union recognition election in a workplace of 300 or more workers in the state in at least the last 15 years.

Building action networks, fighting organization

The blitz, too, was an effort to open political space to challenge the reactionary climate and let workers know that other workers in the area are organizing to build power and fight back. It was likely the first time many of the workplaces targeted for outreach during the blitz were leafletted.

The SWA regularly conducts workplace leafleting in the cities where we are supporting the development of workers assemblies, and in most cases, the leaflettings themselves cause a buzz in the plants that continues for days or weeks after. This experience in Spartanburg was no different: workers have continued to contact the workers assembly after the blitz had concluded.

SWA is not a union and is primarily trying to identify class anger when out on the gates. The organization is focused on identifying, developing, and connecting rank-and-file worker leaders across locations and sectors into action networks, by geography (workers assemblies), industry (regional industrial councils), or otherwise. The workers engaged through these types of leaflettings are connected to other workers organizing via the workers assembly, who in turn support their efforts to begin building a committee in their own workplaces.

Instead of the shop-by-shop, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election-only approach that has become the dominant organizing methodology of the major unions, SWA draws lessons from the periods of upsurge that led to waves of worker militancy and organization, and the conditions that preceded it. In numerous examples—notably the Flint Sit Down Strike that led to the formation of the UAW, or the work of Local 22 and Black tobacco workers in Winston Salem, NC, who organized the world’s largest cigarette manufacturer, RJ Reynolds – a similar method of building networks of leaders across workplaces, who had developed a layer of active coworkers around them, was employed. By slowly developing shop floor organization and associated networks across industries, workers were able to take advantage when conditions changed and a breakthrough moment emerged. The importance of building broader alliances between workplace fights and communities cannot be overstated in the South, a critical factor as well in building successful fights in Southern workplaces, often referred to as social movement or community unionism.

Even if union recognition elections matched their pace in 2024—when around 120,000 participated in NLRB-conducted elections—it would take 100 years to organize another 10% of the 120 million private sector workers eligible to participate in such elections.

In a time when many, correctly, point to the decades-long assault on working-class organization by capital and the ensuing crisis of leadership as laying the foundation for the rise of the most extreme right-wing billionaires who have now wrested control of the state apparatus, can we afford to wait to turn the tide?

This type of activity can be replicated and applied by other worker activists in cities across the Southern region and the entire U.S. The Southern Workers Assembly is preparing a “how-to” guide for others interested in organizing leaflet brigades and blitzes in their cities, ideally connected to a workers assembly to anchor ongoing efforts to build leadership, organization, and bottom-up militancy across an expanding number of workplaces.

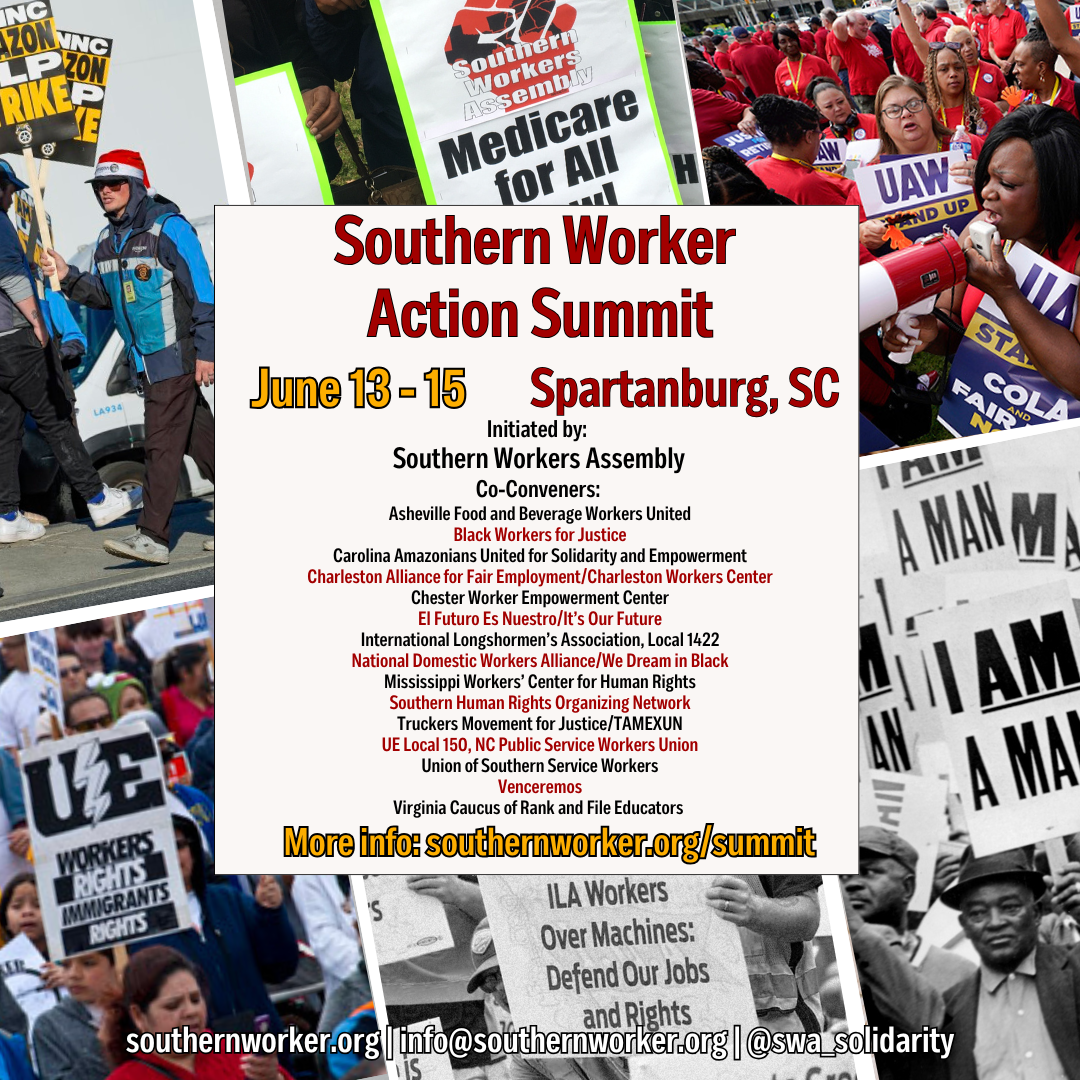

In early summer, SWA is holding a Southern Worker Action Summit, in collaboration with thirteen other Southern worker organizations from key sectors in the region, to bring together a wide array of rank-and-file workers in Spartanburg, SC, on June 13-15. The gathering will take up these urgent questions of building solidarity towards developing a fighting, combative working class movement in this challenging period and addressing more collective efforts towards organizing the unorganized.