Southern politicians have gone out of their way in word and action to make clear they stand on the side of big business and racism as they’ve recently lamented that the “Alabama [ie – Southern] model for success is under attack” and vowing to “fight unions to the gates of hell.”

Nearly two hundred rank and filers who are developing a movement of workers in the South that can build power to make these politicians’ fears a reality gathered in Charlotte, NC on May 17 – 19 for the 2024 Southern Worker School. These convenings are the annual organizing conference of the Southern Workers Assembly network, which includes local workers assemblies, worker organizations, and other workers from various sectors and states throughout the region.

As the upsurge in worker organizing and fightback continues to expand – most notably represented in the UAW drives across the auto industry – the 2024 elections loom and the broader social movement to end the U.S. supported Israeli genocide in Palestine widens and spread, the gathering came at particularly timely juncture to assess conditions and develop united plans for advancing in this period.

“Being in a room with such a diverse group of workers, we can consider that a real cross section of the American landscape. It felt like a new beginning of the labor movement to me, a room filled with people organizing to achieve justice in the workplace, from all walks of life, to make sure we have justice for everyone regardless of race, gender, etc,” remarked Jamie Muhammad, Vice President of the International Longshoremen’s Association Local 1414 in Savannah, Georgia. “It was powerful, too, to see so many people wearing keffiyehs and showing solidarity with Palestine. Those are the type of people who look at the news and are aware of everyone’s suffering and want equality for everyone. I’ve never been in a room like that before. When the working people in the South rise up and we come together on a common cause, we can lead the rest of the nation where it needs to go.”

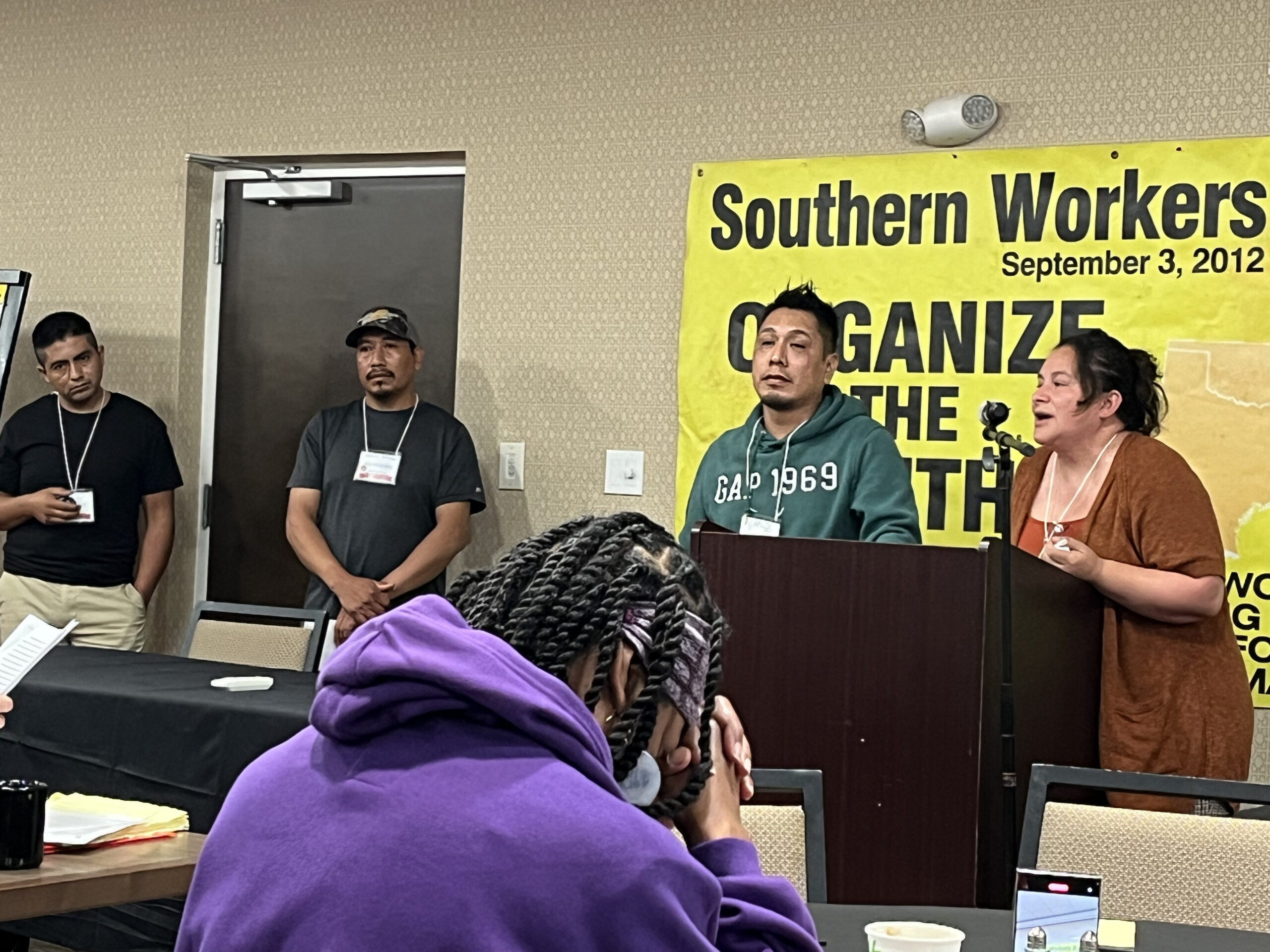

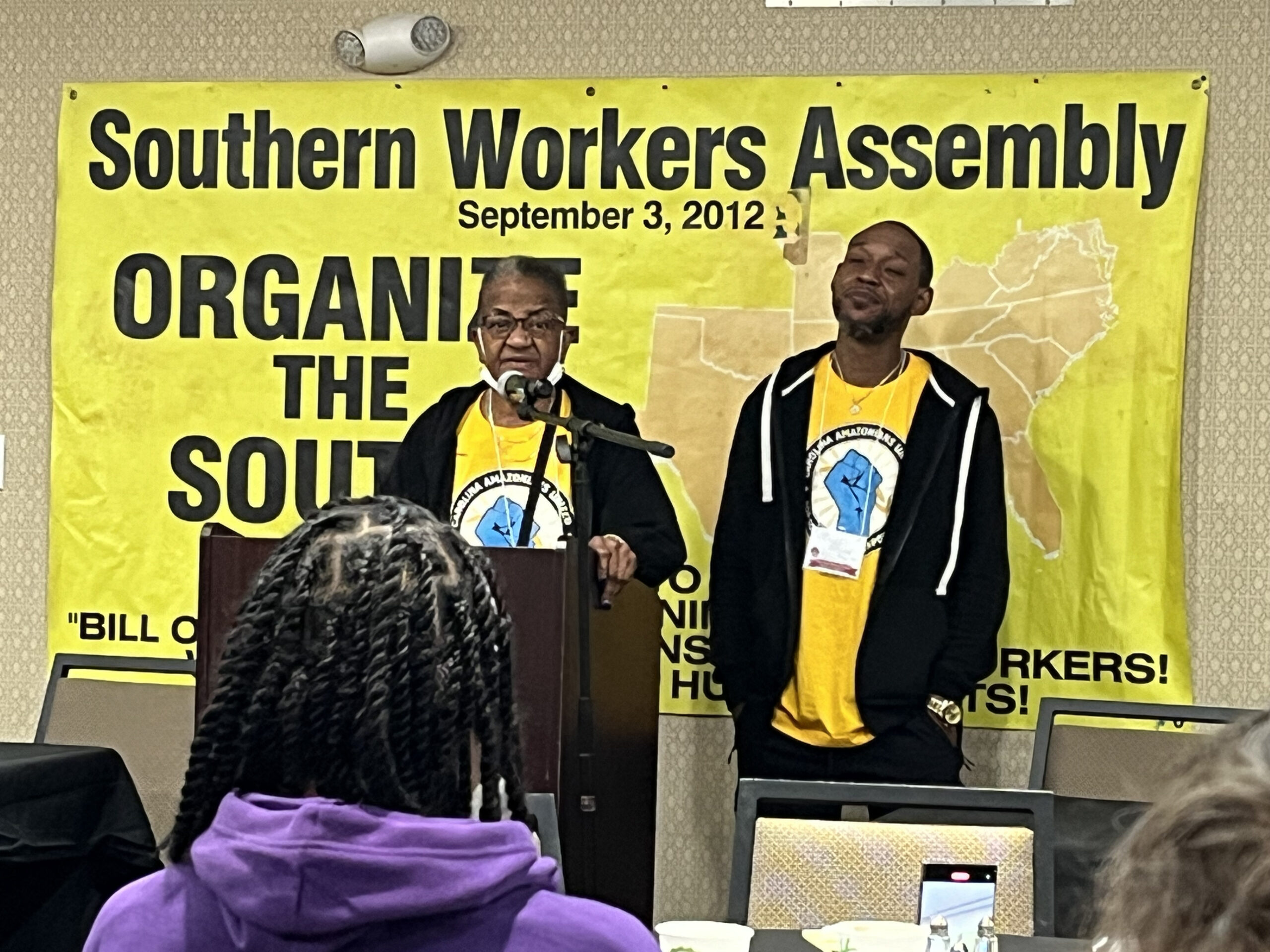

This was the largest worker school convened by the Southern Workers Assembly to date, and included delegations and participation from: El Futuro Es Nuestro/It’s Our Future; Siembra NC; United Campus Workers; UAW; ILA Local 1422; ILA Local 1414; Truckers Movement for Justice (TMJ); UE Local 150; UE Local 111; Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW); National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA); Carolina Amazonians United for Solidarity & Empowerment (CAUSE); Duke Graduate Students Union (DGSU); National Nurses United; and several locals of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW), among others.

Building a movement & worker networks

The opening session of the school kicked off only hours after the result of the vote by Mercedes workers in Alabama on whether to join the UAW was concluded. This opening panel discussion sought to offer some assessment of the organizing across the South, while raising some specific examples and practices from worker network building outside the context of a solely NLRB election approach.

The panel included Ashaki Binta from Black Workers for Justice (BWFJ); Corey Hill, president of UAW Local 3520 and chair of the Daimler Truck North America Council; Dominic Harris, president of the Charlotte Chapter of UE Local 150; Miranda Escalante, Asheville Food and Beverage Workers United (AFBU); and TaShira Smith, a founding member of the Union of Southern Service Workers (USSW).

Ed Bruno, a member of the SWA Coordinating Committee, offered these remarks at the discussion’s opening, saying: “The SWA congratulates the UAW for the election at Volkswagen and Mercedes. The vote counting doesn’t matter. What matters is the workers’ and the UAW’s motivation, willingness, and resources to organize the Southern auto industry.”

Bruno continued, noting, “The Southern auto industry will not be organized one election at a time, nor will the hospital industry or logistics or any industry. We encourage other unions to follow their example. The UAW founding in the 1930s was based on sit-down strikes that were multi-corporation, multi-location efforts to organize the entire auto industry. That’s the way the modern labor movement was formed. And that’s the way the South will be organized today.”

Ashaki Binta expanded on these points, drawing on the 40 year history of Black Workers for Justice organizing workers in North Carolina, noting, “Through our experience, we learned that traditional methods of trade union organizing would not work in the South. Understanding the political and economic structure of the South, that was built to maintain the region as a cheap labor market for capital, and the oppression of Black people in particular as the basis for that market, impacting all other workers. Sixty percent of Black workers live in the U.S. South. The question of building power for working people has to be the objective and basis of our work. The experience of the UAW is extremely important and we are looking forward to learning all that we can from their work. Even so, there are still millions of workers in the South that need to be organized.”

USSW, AFBU, and UE150 worker leaders all contributed lessons of how they’ve developed worker networks that prioritize collective action and movement building, utilizing this central orientation to win on issues and grow their organizations.

Joining this discussion just over a week after the record contract won by Daimler Truck North America workers was overwhelmingly ratified, Local 3520 President Hill reminded everyone that, “We won a record contract. But the war has just begun. The thing of it is, they always change the game plan on us to keep us divided. Divided no more we will be. When we stand together that’s where our strength comes from. We took six locals and brought them together. Not the bargaining committee, not the leadership, but the workers won that contract. They proved they could set out and walk that line and do what they needed to do. But we have a lot of work to do.”

Higher levels of consciousness, coordinated collective actions

The remainder of the weekend focused on deepening sector-based networks, sharing out organizing reports on lessons from workers assemblies and workplace committees, political education, and assessing interventions made by workers across the SWA network in solidarity with Palestine – from organizing contingents in demonstrations, education workers and others building solidarity with student encampments, moving ceasefire resolutions through union locals and city councils, and more.

“It was powerful to see how so many other workers are thinking like me and fighting to make change in the workplace,” said Shenika Brown, a truck driver from Memphis, TN, and a member of Truckers Movement for Justice.

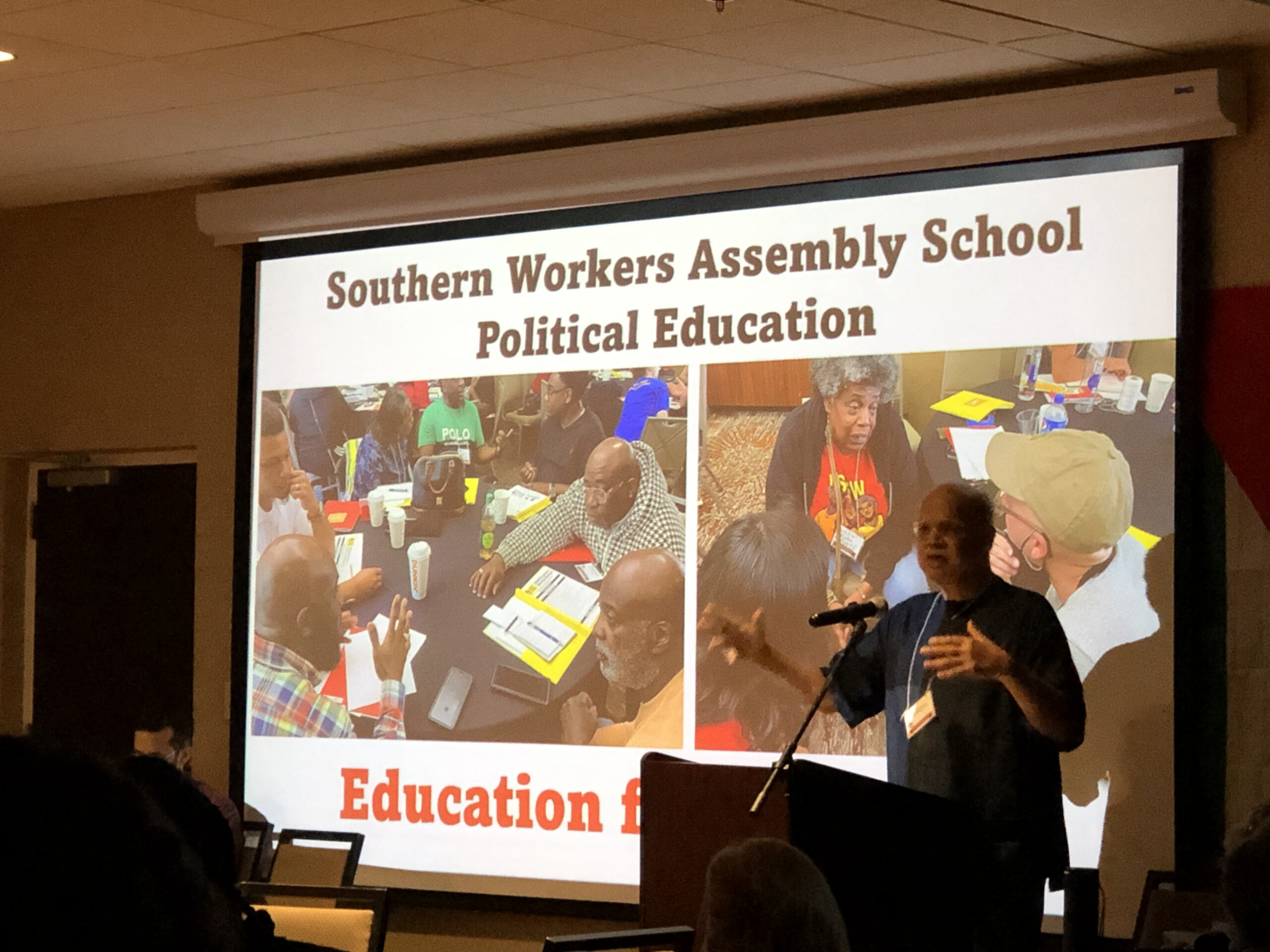

During the political education discussion, led by Abdul Alkalimat of the SWA Education Committee, attention was given to analyzing and assessing the political economy of the South. Alkalimat broke down the concepts of the base – the productive forces – and superstructure – the consumption of commodities/services, social reproduction, ideas, etc – of the economy. In particular, there are many changes occurring in the base of the Southern economy in this period, with large capital investments in manufacturing and electric vehicle production, that are worth the attention of worker cadre to understand and incorporate into our strategic thinking.

In light of these developments, the Southern Workers Assembly has recently launched a program aimed at recruiting workers to get jobs in some of these growing, strategic sectors of the Southern economy. This program was discussed in some detail during the weekend.

There was also a great deal of discussion of political power and how it’s developed, in light of the 2024 elections. The Southern Workers Assembly’s nine point Worker Power Program was raised as a way for workers to make independent political interventions that are connected to the primary objective of building organization and power in the workplace.

Workers from the logistics, manufacturing, public, building trades, healthcare, education, and service sectors held breakout discussions on Saturday afternoon, during which time they were able to share about the work and fights they’d been engaged in and identify more opportunities for coordination going forward.

“At each of the past two SWA worker schools, there’ve been industry breakouts where I’ve met multiple union brothers and sisters from my sector. And these are members who’re already committed, long-term, in seeing a real united working class force in the South. An organization that can pull in building trades workers like that is, frankly, rare. I come away from these weekends with people who live states away but who I can consistently rely on for educated strategies and resources. The value of that is immeasurable,” said Chris Anders, a rank & file member of IBEW LU 666 in Richmond, VA.

At the November 2023 worker school, service and education workers formed industry councils that have met on a semi-regular basis since that time, and made plans to continue to coordinate coming out of the most recent school. In addition, public sector workers from Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina formed a pubic sector council that intends to meet going forward.

“To see teachers and rank and filers from Amazon and other places, even though we work in different industries to see and hear that we have a common thread to be treated with dignity and respect was powerful. We’re all fighting to make our employers recognize our value and to assert that we do have a voice. To see all of us coming together was amazing, united around a basic thread that we want to be treated with dignity and respect and should be paid what we are worth. We’re human beings, not robots,” Mary Hill, vice president and co-founder of CAUSE, reflected. “I was especially encouraged to build solidarity with migrant workers and to see so many young people at the worker school. The group we brought from CAUSE was largely new members. We’re not just fighting our own struggle at different workplaces, we’re building a movement and it’s a legacy we’re passing on to the younger generations coming behind us. It gives me hope for the future to see younger generations getting involved in struggles at their workplaces.”

The worker school contributed towards advancing the deepening of worker networks across the region, and in addition to providing space for exchanges and coordination among the ten active workers assemblies, workers from more than half a dozen other cities were in attendance and are making plans to begin building assemblies in their cities coming out of the gathering.

The movement to organize the South marches forward.